Five Key Components of Strategic Sourcing

For growth companies, aggressively leveraging opportunities to lower procurement costs can be the difference between profit and loss. Growth companies — entrepreneurial startups that have reached, say, $200 million in revenue — almost always have interesting and exciting success stories to tell about building their products and customer bases.

For any such company, however, there comes a time when it needs focus on financial and operational results, not just growth.

Most growth companies want to improve in these areas, but many shy away from instituting bureaucratic management policies that they rightly feel could undermine the free-spirited company culture that contributed to their success. One tangible thing they can do, without upsetting the cultural apple cart, is consider a new approach to purchasing.

We see $200 million in revenue as a kind of tipping point for companies to turn to a more coordinated approach to sourcing. People costs often represent roughly 60% of overall costs, but the remaining $80 million is enough for a company to begin leveraging economies of scale on equipment, technology, services, etc. For a company of that size, saving, say, $3 million can easily make the difference between a red or black bottom line.

Of course, the company should take care not to pare costs unwisely. Notably, cutting perks and extras — free lunch on Fridays, happy hours, year-end bonuses — might seem to be an obvious tactic, but it may not be a sound one.

For most companies, there aren’t enough people in the job market to fill all of their open positions. And no company wants to lose its existing good people. So it’s important for growth companies to subtly drive out costs in a manner that has the least impact on the organization and its culture. Say an organization has insufficient insight into whether it’s paying a fair and equitable amount for equipment and services in relation to the market. This often occurs where a noncentralized purchasing approach is tolerated, with individual stakeholders and users maintaining their own vendor relationships and negotiating their own contracts.

Sometimes, especially in the case of longtime trusted vendors, it’s hard for these stakeholders to relinquish control. Sometimes, people doing procurement piecemeal within the organization don’t have proper negotiating skills. Most often, they lack the time and resources to research the best market prices on products, technologies or services. None of that is hard to understand. For someone who values a certain software program, it’s easy fall into the trap of thinking, “I can only get that from this vendor, so I have to pay whatever they want.”

What does strategic sourcing entail? We see it as a combination of five main components.

Contract Management

This is an organizational process of centralizing all of the company’s contracts, and understanding when they come due and what’s in them. Many companies fail to keep track of their many vendor contracts, so they are automatically renewed, often with ill consequences like paying for technology that’s no longer being used. This problem can be significantly worse if the company is growing through acquisitions, in which case there are likely to be multiple contracts with the same vendor.

The best thing to do, after putting in place a process of organizing contracts, is to start having internal conversations about those coming due in four months. Building in that advance time means you can have conversations that establish who the supplier is, whether it’s still needed, and whether it should be replaced with something else. This well arms a company heading into contract negotiations.

Utilization Management

What are you paying for — and again, are you actually using it?

In a growth company, business moves quickly. There’s great demand for growth. There are constant technology initiatives; processing power is doubling at regular intervals, meaning companies can do more with less. As a result, it’s not unusual for companies to be paying (as per terms of their contracts) for unused data center space, or for technologies they formerly used on an old platform. By starting a due-diligence process well before the expiration of utilization-management contracts (where the vendor payment is calculated as the number of unites consumed for a given unit price), companies can take the time to explore them so as to discern what’s needed and what isn’t. Of the projected savings companies can expect to realize from strategic sourcing, perhaps 60% is likely to be from utilization improvement.

Vendor Strategy Development

Understand your vendors and what you’re buying from whom. For example, say a company spends $5 million a year on temporary labor. Whoever needs a resource calls an agency.

Eventually the company is using 20 vendors to fill similar positions, at a variety of rates. In fact, there are cases where the same resource type is charged at different rates by the same vendor. By taking a strategic view of this spend, the company can identify opportunities to establish a standard rate schedule and consolidate to a few key vendors. Preferred vendors appreciate their status and provide improved service while the company pays an average of perhaps 15% less for their temporary resources.

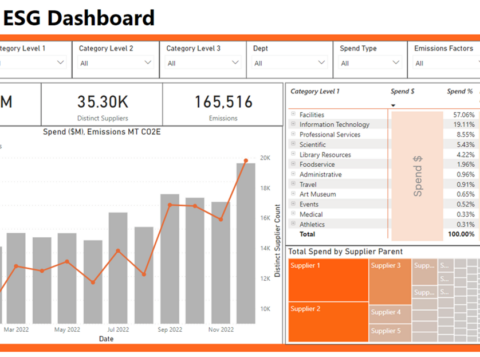

Spend Aggregation

If a business unit needs to buy 100 laptops, standard procedure is to call around to see who has the best deal on laptops at that moment in time. But companywide, there’s demand for a lot more than 100 laptops, as well as all kinds of other IT hardware and software that, if aggregated, would allow the company to develop leverage with vendors.

Spend aggregation not only leads to significantly better pricing, it helps streamline the procurement process. Instead of having to make calls and negotiate all those little purchases, a company can set up a fair, advantageous, equitable, pre-determined schedule with the supplier.

We’ve seen this done with IT value-added resellers, temporary labor, even custom print jobs. Aggregating the spend looks not only at what you’re buying right now, but also at what you project to buy. It thus builds leverage: “We’re not coming to you with $50,000 spend; we are a $3 million-a-year customer and we expect to be treated like one.”

Objectively Informed Negotiation

Going back to the legacy relationships with suppliers, a company that’s objective about the broader market is something most vendors aren’t used to. That can be deployed to great effect.

Without such market intelligence, vendors can easily convince companies that they’re getting a good deal, whereas that might not necessarily be the case. Bottom line, by taking a more centralized and strategic approach to supplier management, it’s possible to drive down cost without putting a crimp on your internal culture.

John Marchisin are Mark O’Hara are managing directors at AArete, a global consultancy specializing in data-informed performance improvement. They can be reached at jmarchisin@aarete.com and mohara@aarete.com