How Will Telehealth Change After the Pandemic?

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, telehealth was more of a stretch goal than a reality for most providers despite the seeming prevalence of video conferencing.

Traditionally, although technology barriers were cited as a limiting factor, the gradual widespread adoption of high-speed internet and smartphones overcame that obstacle for most patients, but some of those least able to get to doctors, such as the elderly, may still require some assistance connecting.

With the bandwidth and hardware questions out of the way, technical concerns around security remained; highly secure systems that comply with HIPAA privacy requirements bring added costs that meant only larger practices and health systems invested in them. Beyond technology, other obstacles included credentialing and licensing requirements, like the prerequisite that a patient have an established relationship with a primary care physician, as well as reimbursement policies.

But when the pandemic hit, the realization that person-to-person contact needed to be significantly reduced meant some regulations under the purview of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) were quickly relaxed for the short term to ensure access to healthcare, which contributed to a rapid rise in telehealth use.

Over the course of the pandemic, insurers have paid out anywhere from two to ten times more per month for telehealth services in 2020 compared to 2019, with a huge surge in the spring, a reduction over the summer, and then a new resurgence as COVID cases spiked in the fall and winter.

In parallel to the manner in which companies that had resisted telecommuting came to learn how effectively people were able to work from home following this past spring’s stay-at-home orders, patients, providers and payers alike saw that telehealth, too, worked fairly well for all parties involved. But as the US looks to emerge from the pandemic, should we expect the rules for telehealth to remain relaxed? Or will telehealth become a thing people look back amusedly upon the way we will all remember practices like stocking up on toilet paper and attending online coffee breaks and happy hours? While we certainly expect to see some degree of tightening, we predict that telehealth usage will remain vastly increased compared to pre-pandemic times.

The expansion of telehealth has benefited many patients. People with chronic conditions such as diabetes and many types of heart disease can be effectively monitored with the aid of other technology like blood glucose monitors, EKGs and pulse oximeters. So, too, can newly discharged patients; in fact, these technologies allow for earlier hospital discharge as these monitoring devices substitute for in-hospital “nurse checks.” The growing use of these devices, increasingly employed by families to keep an eye on distant relatives during the various lockdowns, has ushered in an accelerated rate of adoption of remote monitoring that is likely here to stay.

These monitors, combined with the video interactions that characterize telehealth activity, are highly effective and efficient ways to provide high-quality patient care at reduced cost. Effective mental health treatment, occupational and speech therapy, and even eye exams are also being provided through telehealth technologies.

But the quality of patient care provided through telehealth ties into one of the reasons that we expect to see a reduction in telehealth following a return to relative normalcy. Specifically, we think that the following factors will result in a mild scale-back of telehealth:

- The need for all healthcare communications to be HIPAA compliant

- The requirement that there be an established doctor-patient relationship

- The return to reduced reimbursement rates for telehealth visits

- A mild reduction in the current provider specialty expansion

- Increased anti-fraud, waste and abuse efforts

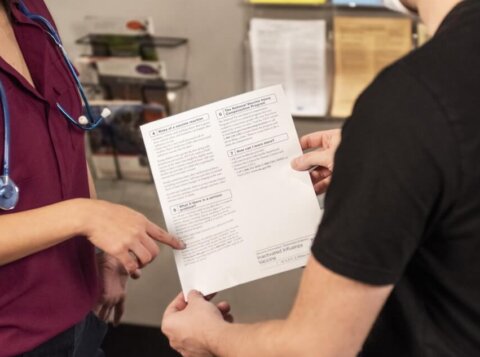

Among the changes that made the current telehealth expansion possible was a loosening of the standards around HIPAA violations. Specifically, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) waived penalties for any such violations that occurred in the use of telehealth. Post-pandemic, we anticipate that previous security standards will be reinstated and full HIPAA privacy protections brought back as the healthcare system returns to its more traditional regulatory footing. It will be incumbent on the telehealth solution providers to maintain and or exceed HIPPA standards.

Secondly, we predict that HHS will once again enforce the requirement that there be an existing relationship between a patient and a practice before telehealth use between the two parties is permitted. As with HIPAA requirements, HHS did not actually waive this rule during the pandemic; rather, it made it clear that there would be no audits or reprimands related to this requirement over this time. It seems reasonable to expect that something akin to the old rule, in which a patient was considered “new” to a practice if she or he had not been seen by anyone there in the last three years, will be reinstated, with some likely leniency for some specific billing codes or types of new patients.

During the pandemic, providers were instructed to charge telehealth visits at the same rate as in-person visits in order to encourage providers to use telehealth. This practice will almost certainly cease following the pandemic, when most telehealth activity will likely once again be billed at 80 percent the rate of an in-office visit due to the reduced overhead associated with telemedicine.

Where telehealth previously was only permitted for practitioners like MDs, nurse practitioners and physician’s assistants, a range of others were allowed to utilize it during the pandemic, including physical and occupational therapists, speech therapists, social workers, psychiatrists and psychologists. The success around most of this expansion in terms of quality of care means that it is likely that it will mostly remain in place except for some specific codes for which quality of care mandates in-person visits.

Finally, attempts to stamp out fraud, waste and abuse will be more robustly applied to telehealth activity. For example, auditors and investigators are hard at work to identify outlier providers scheduling unnecessary follow-up visits, up-coding e-visits or virtual check-ins to telehealth visits, billing for unlikely tele-treatments such as personal care, or charging for excessive therapy visits. In addition, a few unscrupulous telemarketers have gone “fishing” and persuaded Medicare patients to share their member information, then used this data to do things like schedule unnecessary tests and order unneeded equipment.

Some abuse has also taken place with pharmaceuticals being over-dispensed because early refills have been allowed and increased quantities of medications have been disbursed under the guise of reducing the number of visits patients make to pharmacies. Considering how pricey some brand-name medications are, a single wasteful pharmaceutical claim can be highly lucrative.

Many of these issues point to the need for tighter regulations to drive best practices in telehealth and to mature the services that help support remote medical care.

There is no doubt that one unforeseen positive resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic has been an expansion of telehealth both in terms of patients’ ability to access it and the healthcare services they can receive. Because of the success of this expansion, we see a future in which people spend less time traveling to and from healthcare facilities while still receiving high-quality care virtually from their homes and other remote locations.

This article was published in Managed Healthcare Executive.